Cheonggyecheon Stream restoration, Seoul - © Korea Trade Organization

Cheonggyecheon Stream restoration, Seoul - © Korea Trade Organization Cheonggyecheon Stream : Before and After - © CABE/ Design Council

Cheonggyecheon Stream : Before and After - © CABE/ Design Council Cheonggyecheon Stream: Functions - © CABE/ Design Council

Cheonggyecheon Stream: Functions - © CABE/ Design Council

City

Seoul

Main actors

City Government, Private Sector

Project area

Neighborhood or district

Duration

2003 - 2005

Cheonggyecheon Stream has been transformed into a 10.9 km (7.0 miles) modern public recreation space in downtown Seoul.

Historically the downtown area was the economic centre and one of the most vibrant business districts in Seoul. The elevated highway covering the stream acted as an artery for transport and logistics. However, over time, the overpass deteriorated and many safety issues were identified. Subsequently, the need was growing for an eco-friendly urban renewal strategy to keep up with social changes including a shifting economic focus and changing residential pattern.

Against this backdrop, the Seoul Metropolitan Government undertook a major urban renewal project including the restoration of the stream. The aim of the project was to restore a decrepit public space and create a waterfront in the downtown area, restore the historical apects and improve the environment. Furthermore, it would revitalize the city by attracting more more business activities and inturn private investment and encourage citizens to relocate. Despite initial criticism and skeptism, the project is highly successful, strengthening the resilience of the eco-system and providing a useful green space for the citizens.

Sustainable Transport Award

This project was awarded the 'Sustainable Transport Award' in 2006.

-

Safety issue of the elevated highway

Safety issue triggered the initial discussions on the restoration of Cheonggyecheon. The structure of the covering road and the elevated highway was deteriorating, causing serious safety risks since the 1990s. A study conducted by the Korean Society of Civil Engineers in 1991-92 found corrosion of the steel frame inside the highway and structural flaws in its upper plate and repair work was conducted for a 2-kilometer sector of it. The 30-year-old road covering Cheonggyecheon required substantial amounts of money for continuing maintenance and repair. Another safety checkup conducted from August 2000 to May 2001 revealed that cracks and exfoliation persisted in the upper slab, while the load carrying capacity was insufficient due to the worn-out concrete beams. As a result, a full-scale reconstruction was inevitable. Reconstruction was estimated to cost 93 billion won over three years. In 2001, the city government of Seoul annoucned a plan to demolish the elevated highway and reconstruct it with work commecing in August 2002.

-

Shift from maintaining the elevated highway to restoring the stream

Since the 1960s, development, construction, production and efficiency have been priorities for the Seoul Metropolitan Government. However, starting in the 1990s, the urban planning paradigm shifted to focus on people, history, nature and environment, as the public consciousness changed over the course of socio-economic development. Discussions on justification, necessity and significance of restoring Cheonggyechon icrease in the late 1990s. Restoration became a major topic during the mayoral election campaign in early 2002. Over the course of political debate, the direction of the initial plan shifted from reconstruction of the elevated highway to restoration of the stream. There were still many choices and decisions to make between idealistic goals―historical values, eco-friendliness, optimization in each sector, and the practical considerations―cost, time, optimization in the entirety, minimization of inconvenience among the neighboring businesses, and phased approach.

-

Public-private partnership issue

While Cheonggyecheon itself is a public place, the surrounding area were privately owned properties. To include the private properties in the project the budget would not only have to signficantly increase, it would require time to deal with administrative matters such as revision of urban plans and compensation. Therefore, the Seoul municipality decided that the restoration work itself would exclusively cover the public land within Cheonggye to ensure the feasibility of the project. In this approach, the public and private sectors had to take their respective role in turn. Firstly, the city government was to demolish the coverage and the elevated highway, create an eco-friendly waterfront and restore the historical value of the stream through public investment. The ripple effect of restoration would help revitalization of the downtown and neighboring area, which will be conducted in partnership with the private sector in a way that both public and private sectors could benefit.

Major components of Cheonggyecheon restoration plan

The restoration had to consider diverse factors of Cheonggyecheon in historical, structural and functional aspects. Restoration of historical landmarks such as old bridges and stoneworks was one of the main concerns of citizens. The restored stream also needed to have enough capacity to deal with floods, as abnormal rain fall has become more frequent due to climate change. In addition, it was necessary to maintain its previous role for transportation and sewage. Most of all, the project had to create a better natural environment, which was the biggest aspiration of the citizens. To this end, it was imperative to secure water supply for the stream, which turned out to be a difficult task.

-

Restoration of historical values

Restoration of historical values was important in justifying the project and ensuring citizens' support. The Seoul municipality agreed to preserve all heritage aspects excavated during the construction. In the actual work, however, the safety of citizens emerged as a bigger priority. The municipality's principle was to restore the originality to the extent in which citizens' safety from flood and other risks is ensured. However, some members of the citizens' committee and some civil associations insisted that the stream be restored entirely in its originality. Such a difference sharpened in the phase of actual work. As specific concerns emerged with regard to flood control, transportation and negotiations with the neighbor businesses, some of them became incompatible with the preservation of historical remains.One of the biggest issues was the restoration of Gwangtonggyo bridge. There was a strong argument to restore it to its original shape, which required an extensive work. In order to secure enough cross-sectional area for the water flow, in other words discharge area, it was necessary to purchase private lands in the bridge's vicinity, but it was practically impossible. Insufficient area for discharge would lead to failure in safety and flood control. The city finally decided to rebuild Gwangtonggyo at a spot 150m away from the original location to the upstream, in a belief that restoration at the original location will be possible in the future when a better condition is prepared. Restoration of Supyogyo in its originality might incur similar problems. The Cultural Heritage Committee of Seoul concluded to leave Supyogyo where it was, in the Jangchungdan Park, in order to avoid deterioration of the original stones. At 27.5m, the original Supyogyo was longer than the width of the restored stream (22m) at the point. To restore it in the original shape, the city had to expropriate private properties in the vicinity, which would inevitably prolong the construction and cause more inconvenience for the neighboring businesses. Therefore, the municipality decided to restore Supyogyo in the future, once favorable conditions are made available. See attached fig.

-

Flood prevention and safety measures

Although the restoration of Cheonggyecheon was initiated in a bid to restore historical and environmental values, the safety issues including flood prevention became significant during the work process. The city set the target flood recurrence interval of 200 years. Given that other 2nd-grade local streams were managed based on 50-year interval assumption, it was a decision to better ensure the citizens' safety by securing sufficient stream capacity to deal with local torrential rainfalls. The city also strived to secure discharge areas by excavating beneath both banks.

-

Sewerage treatment

A substantial number of sewerage pipes were buried near Cheonggyecheon, as sewage water from the downtown area has traditionally gathered along it. Finding ways to treat such sewage was a precondition to the restoration. Since the existing sewerage system was often combined with the rainwater collection system before it reached the stream, it was practically impossible to segregate sewage from rainwater. Separation between them was also inappropriate because the downtown rainwater flowing into Cheonggyecheon was highly polluted. Therefore, the municipality adopted a double-box system. The sewage would be treated in a combined system and highly-polluted initial rainfall would be segregated into a separate pipeline to be treated at the treatment facilities, not flowing into the stream.

-

Water supply and its quality

Cheonggyecheon was historically a ephemeral stream. It was difficult to draw water from the vicinity, because the underground water level became lower due to urbanization. Given that there was no valley water from the upstream, an artificial supply of water was inevitable to maintain the stream. The Hangang (Han River) and the groundwater discharged from nearby subway stations were selected as water sources. The Korea Water Resources Corporation attempted to tax the Seoul municipality for drawing water from Hangang, but it was eventually discounted by 100% on the grounds that the water would be used for the public interest. As for the water quality, the water treatment was decided as secondary treatment considering relevant conditions and costs.

As the city aimed to have the project recognized as a public one, it was important to obtain approval from the Seoul Metropolitan Council. To secure the budget of KRW 384 billion for the restoration, the municipality utilized KRW 100 billion that was initially assigned for the overall renovation of Cheonggye elevated highway. It also saved approximately KRW 100.4 billion by downsizing less urgent projects and introducing creative work procedures to enhance efficiency of the city administration. The rest of the budget was secured from the city's general accounting. The project fund for Samilgyo, Mojeongyo, Gwangtonggyo and Jangtonggyo was donated, allowing the municipality to save KRW 8.2 from the budget. In total, KRW 384.4 was invested in the project. The amount was approximately 1% of the total budget of the Seoul municipality, compared to other waterway restoration projects in Korea and abroad, the Cheonggyecheon restoration project was highly economical.

-

Improvement of environment:

The creation of a wind corridor, reduction of heat island effect, better air quality, and restoration of the natural environment, and reduced traffic volume in the Cheonggyecheon area significantly reduced the concentration of fine dust (PM-10), NO2, volatile organic compound (VOC) and other air pollutant, shorty after the restoration. The heat island effect in the downtown area also declined. The temperature of the Cheonggyecheon area before the restoration was 2.2℃ higher than the average of Seoul, it declined to 1.3℃ after the restoration, dropping by 8 to 18%. The temperature of green point within the stream was 0.9℃ lower than the neighboring area, As the air-blocking elevated highway disappeared, a wind corridor was established and the creation of a stream affected the neighboring environment. The ecosystem was also restored as wildlife fish species, birds, insects and plants increased.

-

Flood control

Cheonggyecheon is the lowest-lying area in the old downtown area with an extensive basin to collect rainwater and gently sloped banks that make it a highly flooding-prone stream. Overflow occurred for two consecutive years before the restoration began, causing damage in the downtown area. Given that torrential rainfall is frequent in Seoul, the discharge area of the restored stream was designed on the basis of 200-year recurrence interval. While the estimation at 200-year recurrence interval had revealed that most of the low-lying area around Cheonggyecheon had been subject to inundation before the restoration, there was no report of flooding due to lack of discharge area after the restoration, which means that the vicinity was made free from flooding damage.

-

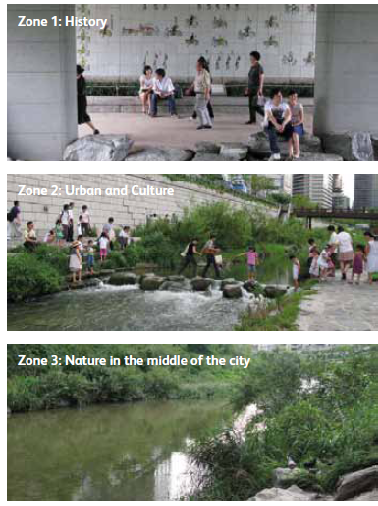

Increased public space, pedestrian-friendly environment, more floating population and tourists

The floating population in the Cheonggyecheon area on weekdays and weekend recorded a significant increase. The increase was larger on weekdays, meaning that citizens visit the stream often in their daily lives. In the 2013 survey, 89% of respondents were on the fence or satisfied with the walking trail along the stream. They were particularly satisfied with the uniqueness of the place itself. However, the survey showed a lower level of satisfaction in accessibility, because the access from the ground level to the stream is limited due to the stream's narrow width. 59/% of citizens surveys sighted the biggest contribution of the restoration was the creation of a place to relax. Cheonggyecheon also became a venue for diverse cultural events: 259 events were hosted in 2005-07, firmly positioning the stream as a place for culture and recreation.

-

Changes in citizens' consciousness

One of the big achievements of the Cheonggyecheon restoration is citizen awareness of the value of the natural environment. Before the restoration project commenced, people already had interest in the natural environment, after witnessing the restored stream and its environment, people's recognition of the value further increased. According to a survey on citizens' willingness to pay for a natural stream before and after the restoration project, the annual economic value of a natural stream appreciated by the citizens jumped from KRW 20,226 to 37,724 per household. The survey confirmed that the citizens of Seoul placed a higher value on the natural environment after experiencing the restored Cheonggyecheon.

Technical Challenge

-

Short construction period, limited budget, and waste recycling

Cheonggyecheon was planned to be demolished and renovated in three years commencing in 2002, during which time inconvenience of neighboring merchants was inevitable. Since the main complaint of neighboring merchants was to minimize the construction period, it became a priority to complete the work as soon as possible. In order to shorten the construction period. the contract for the project was processed in the "fast-track design-build" system.

-

Creative envisioning

"Envisioning" is the keyword in the restoration of Cheonggyecheon. Eliminating 18 of the busiest lanes in the heart of Seoul was certainly beyond imagination, given that car useage eas continually increasing and traffic jams were intensifying. Many people strongly opposed the plan. However, the elimination of roads and the creation of a waterfront made the downtown area more vibrant and environmentally pleasant and the quality of lives of citizens improved, Contrary to the prediction of many experts, the transportation system moved quickly to public transit-oriented, which improved the downtown traffic conditions.

-

Leadership

Leadership is crucial in such a ground-breaking transition. A leader should be able to present a clear vision, run the organization and its human resources in an efficient way, resolve internal skepticism and external conflicts, and communicate and persuade people.

-

Appropriate implementation system and efficient project management

At the initial stage of the project, the citizens' committee comprised of the general public and experts contributed signficantly to setting the project's direction by gathering different opinions and building consensus. The restoration could not be achieved with partial approaches. Coordination between different sectors ―water, road, sewerage, civil engineering, gardening, architecture, urban planning, economics, social affairs and welfare―was crucial to move forward. The municipality appointed a vice-mayor level official to take responsibility for organizing and coordinating the project effectively. The weekly meeting held at 8am every Saturday played a key role in speedy decision-making and resolution of conflicts between different city departments. As a result, the project was successfully completed within the target deadline and without exceeding the budget by a large margin.

-

Public-Private partnership, and the triangular implementation system

It is also noteworthy that a close public-private partnership contributed to the downtown area transformation. The triangular implementation system consisting of the administrative agency to implement the project, a research body to provide expertise and a citizens' committee to gather citizens' opinions worked effectively. Such a practice paved the way for the emergence of collaborative planning in the future urban planning of Seoul.

-

Pros and cons of politicalization

Politicalization of the Cheonggyecheon restoration was complex. While the political momentum certainly drove the restoration project more powerfully, the project became a subject of political controversy, rather than a factor of urban revitalization. It also became a matter of political upheaval in the mayoral election every four years. Despite the necessity of long-term management, the public sector could not fully ensure the consistency in managing the Cheonggyecheon restoration and urban revitalization efforts. It is unfortunate that the task of urban revitalization exclusively fell to private sector, due to the absence of public intervention.

External links / documents

On Map

The Map will be displayed after accepting cookie policy