There are myriad ways issues of social justice and urban development influence each other. Urban planner, Mennatullah Hendawy, advocates for societal justice in the planning and designing of cities.

Hendawy is an urban planner, designer, and researcher, whose work focuses on the intersection of cities, communication, and justice. Hendawy is co-founder of Cairo Urban AI and First Degree Citizens; an initiative that tackles critical socio-legal geography. Having recently completed her Doctoral thesis at the Faculty of Planning, Building, and Environment at Technische Universität Berlin, Germany, Hendaway is also an affiliate of the department of urban planning at Ain Shams University in Cairo.

In the contemporary world, demands for justice in cities are brought to the foreground by urban scholars and practitioners. Various scholars have referred to many metropolises as representing a lack of social and spatial justice demonstrating a heightened sense of urgency to investigate how cities reflect issues of justice and inequalities and how justice can be achieved via the planning and designing of cities.

Justice in urban planning refers to the various social, economic, and spatial qualities that enable fairness in cities.

It is argued that urban planning is essentially concerned with the "conscious creation of a just city" (Fainstein, 2005, pp. 122). This commentary proceeds accordingly from the standpoint that justice "is, and should be, a principal goal of urban planning in all its institutional and grassroots forms" (Bromberg, et al., 2007, p. 1).

I would like to bring to the foreground societal justice involving the social, cultural, and legal community norms as an often missing perspective in the pursue of just cities.

To this end, I base my discussion on the political theorist Heba Ezzat (2013) who asserts that there is a need to advocate not only for social justice but also societal justice. According to the political philosopher Matt Zwolinski, social justice can be defined as "a moral assessment of the way in which wealth, jobs, opportunities and other goods are distributed among different persons or social classes" (2012, min. 1:25).

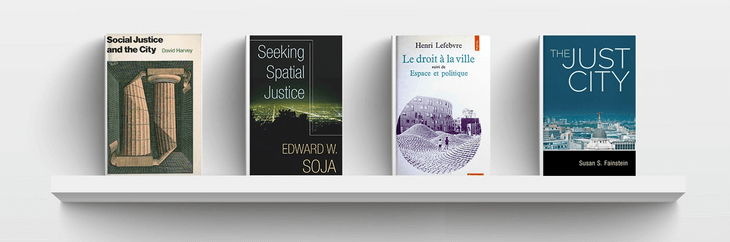

When we look at justice in relation to cities, one can see that starting in the mid-1960s, there has been a consideration for thinking about justice and fairness in urban studies traced back to the conceptualization of Paul Davidoff and Linda Stone Davidoff on advocacy planning in (1965; 1978) which was followed by the work of David Harvey in 1973 on Social justice and the City, Henri Lefebvre's The Right to the City (Le Droit à la ville) in 1968 and his conception of the social production of space in 1974. These movements on alleviating inequalities in cities ignited a spatial turn in the look for justice which was stressed by Edward Soja (2009) who introduced the term ‘spatial justice’ referring to the ways in which justice in society is linked to geography.

These calls for justice and fairness often had direct impact on shaping the needs and aspirations of metropolises worldwide. However, the different demands for justice in urban planning still emerged from, and remain exclusive to, democratic contexts (Fainstein, 2011). Taking Ezzat’s assertion forward, I argue that justice in cities is entangled with justice within societies, and in so doing, making it an entry point to discuss non-democratic and authoritarian-led metropolises.

Societal justice can be defined as the ways in which the embedded ethics, values, and norms in a society enforce or hinder fairness, and justice.

The activist Lynn Malkawy (2018) claims that the lack of societal justice is based on a lack of acceptance of diversity and pluralism. Changing of the conversation from social justice to societal justice entails reversing the idea that justice is only achieved through the state, a government, or a specific powerful actor. Hence, giving power to individuals in a society to shape their present and future. To give an example, it often takes years to transform a rent-legislation that is unfair into one of the stakeholders involved. Yet, the involved actors can still enforce a new system among each other that is fairer. In that sense, corruption in metropolises can be viewed as another example which brings to the forefront the need for societal justice.

The use platform has many example cases of participatory budgeting and redistributive funding that could illustrate the creation of fair processes which represent a society’s commitments to social and spatial justice.

Case studies addressing social and spatial justice on the use platform which can also be looked at from the lens of societal justice:

|

With Citizen participation, the City of Bogota is making the city a safe place for women. The City of Lusaka is building a sustainable working relationship with slum dwellers to create an inclusive city. The City of Medellin is Implementierung a program to increase access and mobility for people with disabilities in the city’s poorest neighbourhoods. The City of Berlin considers the needs of the different lifestyles existent in a city when planning urban development and building projects. The City of Boston teached youth about city building and budgeting process, to gain leadership and professional skills. |

The understanding of justice from a society perspective denotes that the line between ethics and law is diffused and that justice becomes a co-construct whereas each individual/group shares part of the responsibility towards achieving it. As Malkway puts it, in reference to the historical movements against racism in the United States, justice in this view is achieved by the individuals to one another, not (only) as a result of a state intervention.

While the societal understanding of justice might be perceived as one in which less responsibility is placed on governments, it is rather the opposite: It raises questions around the paradoxical role of the state by giving more responsible freedom to societies and have it reflected by its individuals, groups, norms, etc.

Giving freedom to members in a society to shape their just systems and mechanisms is much needed in both democratic and non-democratic metropolises.

According to Ezzat and Malkawy, individual and group initiatives can therefore enable the creation of just societies which I showed as a perquisite for justice in planning and cities. However, more thought, research, practices and policies can investigate further the power dynamics in societies that can or cannot enable them to proceed towards societal justice.

In many urban contexts, "socio-spatial justice" means redressing the compounding effects of poverty with living on urban margins, being exposed to environmental and social hazards (such as pollution and crime.), or being distant from essential health and educational services.

These issues are not easily wished away and this article is an initial viewpoint to embrace “societal justice” as an attempt to address them. I invite not only urban scholars, political and social scientists but also the general public to more critically examine the ways in which justice within and by the society at large co-constructs justice in cities.

We can believe that transformational outcomes are possible when we work together to deconstruct our everyday practices with an engaged commitment to equity and justice, even in not-so-just states.

References

Ava Bromberg; Gegory Morrow; Deirdre Pfeiffer (2007): Editorial Note: Why Spatial Justice?. Critical Planning: A Journal of the UCLA Department of Urban Planning. Los Angeles.

see: http://publicaffairs.ucla.edu/sites/default/files/Editorial_UCLA_Crit_Plan_v14%20copy.pdf

David Harvey (1973): Social Justice and the City. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Edward Soja (2009): ‘The city and spatial justice’, Spatial Justic Conference, Nanterre, Paris, March 12-14, 2008.

Henri Lefebvre. Le droit à la ville. In: L Homme et la société, N. 6, 1967. pp. 29-35.

Paul Davidoff (1965) Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning, Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31:4, 331-338.

see: 10.1080/01944366508978187

Paul Davidoff; Linda Davidoff, (1978). "Advocacy in Urban Planning". In Weber, George H.; McCall, G. J. (eds.). Social Scientists As Advocates: Views From Applied Disciplines. Beverly Hills: SAGE. pp. 99–120.

Susan Fainstein (2005): ‘Planning Theory and the City’, Journal of Planning Education and Research. 25(2), pp. 121-130.

Susan Fainstein (2011): ‘The Just City: Equality, Social Justice and Growth | The New School', The New School, 14 February.

see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5LhpyRhHaD0&t=1667s

For more programs and policies related to social and spatial justice search our case studies data base.