City

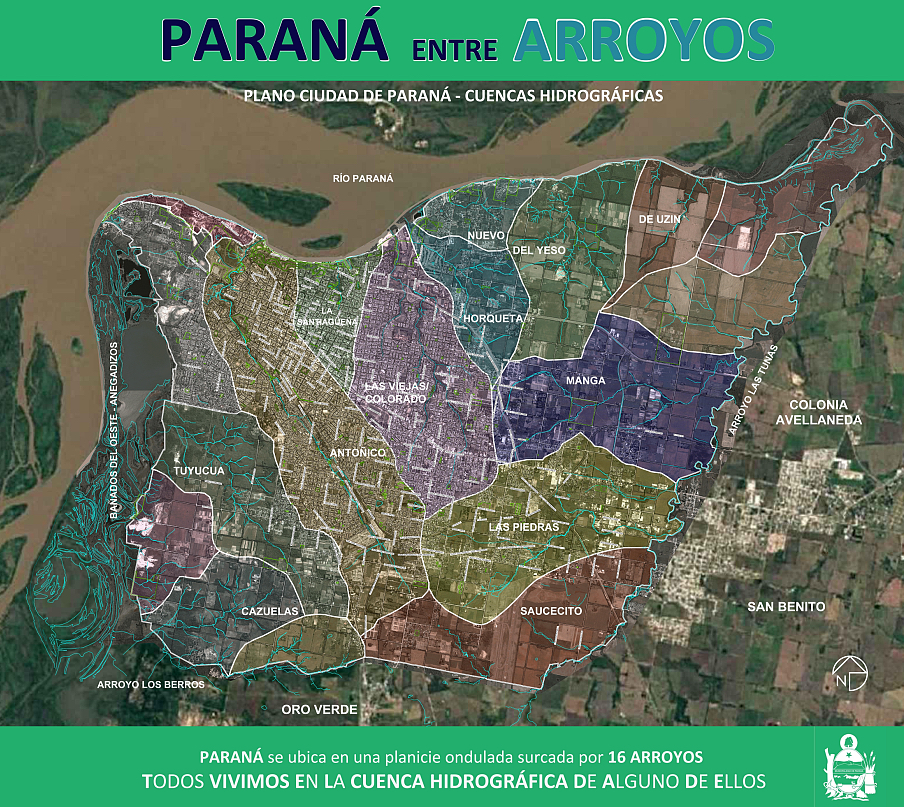

Paraná

Main actors

City Government, Community / Citizen Group, Research Institutes / Universities

Project area

Whole City/Administrative Region

Duration

Ongoing since 2014

Local government and residents work collaboratively on an environmental renewal project.

The City of Paraná has implemented a strategy that facilitates citizen participation in the environmental management of the cities 16 streams. Responding to a resident’s groups concern about the deterioration of the streams, 16 separate committees (Comites de Cuencas) have been established to improve communication between residents, neighbourhood associations and city officials. Working with the Departments of Sustainable Environment and Planning to further develop strategies and plans, the committees have identified challenges and some possible solutions.

In addition, the Committees have facilitated the management and allocation of budgets for the development of linear parks and environmental remediation projects and have also provided public access to information collected by the government, such as maximum flood levels, and water/soil quality surveys for each water basin. Furthermore, the committees have collaborated with local NGOs to promote environmental awareness and increase capacity building in maintenance and cleaning to safeguard the environmental value of the streams.

This case study was contributed from the UCLG Learning Team.

Peer Learning Note #26: Climate Resilience and Urban Development

External links / documents

On Map

The Map will be displayed after accepting cookie policy