City

Bogotá

Main actors

Supranational / Intergovernmental Institutions, NGO / Philanthropy

Project area

other

Duration

2004 - 2014

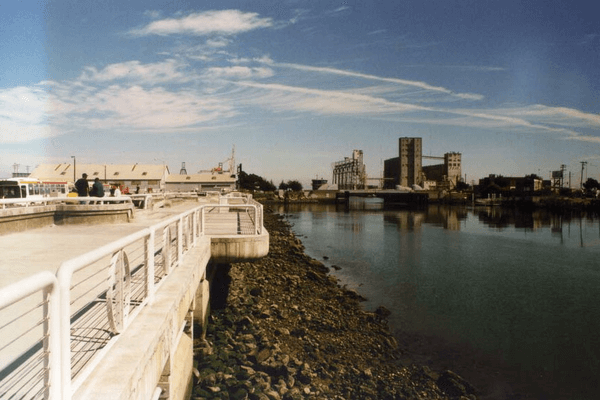

The City of Bogota’s project ‘Camino Imaginado – Imagined Path aims to improve social inclusion for inhabitants in the urban periphery.

The City of Bogota project Camino Imaginado – Imagined Path improves social inclusion for inhabitants in the urban periphery. The main challenge of this project is the deterioration in public spaces in impoverished city outskirts. Prevailing conditions generate processes of social exclusion, violence, insecurity, and neglect for local authorities. For these reasons, IDU, Bogota Institute for Urban Development, builds and restores public spaces, starting with the surroundings of public schools.

The main objectives of this project are providing school access for students and teachers, and creating jobs for rehabilitated young people through cooperation with the Institute for the Protection of Children and Youth (IDIPRON). The overall objective is to increase social integration for marginal people in the Bogotá outskirts and improve their quality of life.

The project’s main steps are finding affected surroundings on the outskirts of Bogota, calculating the costs and benefits of building public spaces, and building or restoring the public spaces required. Since 2004, the project transformed 40,000 sq. m. of public space and created 1,300 jobs for rehabilitated young people. This project was a UN HABITAT best practice case in 2012, and is probably being transferred to other cities in South America needing to face similar challenges.

On Map

The Map will be displayed after accepting cookie policy