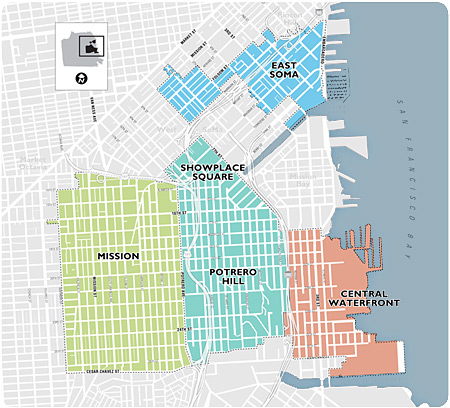

The Eastern Neighborhoods community planning process began in 2001 with the goal of developing new zoning controls for the industrial portions of these neighborhoods. A series of workshops were conducted in each area where stakeholders articulated goals for their neighborhood, considered how new land use regulations (zoning) might promote these goals, and created several rezoning options representing variations on the amount of industrial land to retain for employment and business activity. In February 2004, the Planning Commission established interim policies for East SoMa, the Mission, and Showplace Square/Potrero Hill to be in effect until permanent zoning is established. Starting in 2005, the community planning process expanded to address other issues critical to these communities including affordable housing, transportation, parks and open space, urban design, and community facilities. The Planning Department began working with the neighborhood stakeholders to create Area Plans for each neighborhood to articulate a vision for the future.

The department conducted an extensive outreach program, including several large workshops in each of the neighborhoods, hundreds of smaller meetings and discussions with community groups and individuals, over 15 planning commission hearings, office hours in the neighborhoods, surveys and focus groups with owners of PDR businesses, and a citywide summit on industrial land. Draft Eastern Neighborhood Area Plans were released in December 2007 for public comment. In April 2008, the Planning Commission voted to initiate the adoption process for the Area Plans. In 2008, a series of adoption hearings were held to evaluate the Plans before they were formally adopted and became part of the City's General Plan. As part of this, an extensive public benefits program (including strong affordable housing components) and a commensurate zoning package were also adopted.

The plan entered into force in December 2008; overall the new zoning reduces the part of available land allocated to industries and at the same time increases opportunities for the construction of new housing units. The aim is to counteract current specialization tendencies, to relax the housing market and diversify available housing, as well as to maintain PDR business activities in the Eastern Neighborhoods. The remaining land zoned for industries will be protected, in order to guarantee its availability for that purpose in the future. So the plan increases housing development possibilities without endangering economic development in the Eastern neighborhoods.

Parallel to that, the city planning administration made new regulations enter into force, coinciding and reinforcing the plan’s objectives. These regulations correspond to a constraints and incentives system directed toward investors. First, 15% of new buildings have to be rent or sold at affordable rents/prices. The rate reaches 18% in the case of housing development on former industrial land. Second, if investors include social housing in their program, they obtain density bonuses and thus can increase their return on investment by building higher houses and reducing unitary costs. Moreover, the plan deletes parking minimums that increase building costs for housing units.

The concept “affordable by design” present in the plan consists insofar in a change in the planning paradigm. It refers to the idea that through a higher density of quarters or housing units, it is possible to produce affordable housing. On top of that, investors building new housing units in the neighborhoods will have to pay community improvement fees. It has been estimated that these revenues would cover about one half of the amount (300 million dollars) needed for community improvement.

To foster the implementation of the program, three different groups have been formed, which allow actors to mobilize, as well as represent diversified interests. It concerns: a Plan Implementation Team with a focus on infrastructure; an Interagency Plan implementation Committee with a coordination task and an Eastern neighborhoods citizens advisory Committee.